This Earth One Country/The basis of a planetary economy

The text below this notice was generated by a computer, it still needs to be checked for errors and corrected. If you would like to help, view the original document by clicking the PDF scans along the right side of the page. Click the edit button at the top of this page (notepad and pencil icon) or press Alt+Shift+E to begin making changes. When you are done press "Save changes" at the bottom of the page. |

CHAPTER I

The Basis of a Planetary Economy

N 1834 there was a cabinet crisis in London. Sir Robert Peel, recalled post-haste from Rome, spent thirteen days on the journey, “just the time allowed to a Roman official seventeen hundred years ago.”? Throughout the Christian era, and for millenniums before, there had been practically no increase in travel-speed. Napoleon could not travel faster than Julius Caesar, for the speed of horses and camels on land, and galleys and sailing vessels on the sea remained stationary. Then, suddenly, something happened. Early in the nineteenth century the railroad and the steamship appeared as if to herald a new era. Until about 1840 the average travel speed on land or water did not exceed ten miles per hour. Between 1840 and 1924 travel speed increased fourfold on the seas, and sixfold on land, contracting distances accordingly. Today we can fly across the Atlantic Ocean faster than we could have crossed the English Channel only a few years ago. The world is now actually smaller in travel-time than was Europe under Napoleon, or the thirteen original states under Washington.

- Astley J. H. Goodwin, Communication Has Been Established, London,

Methuen, 1937, p. 214.

13

[Page 14] 14 | This Earth One Country

14 | This Earth One Country

Around 1924 the commercial airplane made its appearance. From any airport we can now reach the farthest city of any land within sixty hours, less than the time required from New York to Albany a century ago. We can fly around the earth faster than a traveller could go from Scotland to London at the time of their union. A new wind tunnel is nearing completion which will test planes flying over 700 miles an hour, approaching the speed of sound itself. Aviation has narrowed the seas into millponds and made the earth a close neighborhood.

This revaluation in travel-time, accelerated still more by the events of the war, means either a multiplication of national rivalries, race antagonisms, and economic warfare, or the greatest opportunity for the creation of a new society. The problem is economic, political, and ethical. The solution is the task of this century.

Trape Maxres Onz Economic Worip

The urge to trade, that is, to exchange the products of one region for those of another, is very great, for it makes life easier. Upon this urge empires have been built, and because of it great wars have been fought. History shows that where trade could best be carried on, there wealth accumulated and civilization developed. Near frequented harbors, navigable rivers, and much-traveled highways cities arose and the arts and sciences flourished. Through barter and trade, community life became possible. Without trade men would still live in the jungle.

In medieval times the town with its surrounding manors

was the economic unit. It was largely self-supporting and was

separated from other towns by trade barriers. The national

[Page 15]

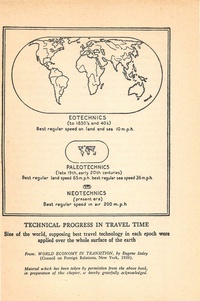

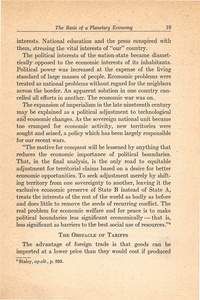

EOTECHNICS (to 1830's and 40%) Best regular speed on land and sea !0 m.p.h.

PALEOTECHNICS (late 19th, early 20th centuries) Best regular land speed 65m.p.h. best regular sea speed 36m.ph

C® NEOTECHNICS

(present era) Best regular speed in air 200 m.p.h

TECHNICAL PROGRESS IN TRAVEL TIME Size of the world, supposing best travel technology in each epoch were applied over the whole surface of the earth

From: WORLD ECONOMY IN TRANSITION, by Eugene Staley (Council on Foreign Relations, New York, 1939).

Material which has been taken by permission from the above book,

in preparation of this chapter, 1s hereby gratefully acknowledged.

[Page 16] 16 This Earth One Country

16 This Earth One Country

economic unit developed later, from the fourteenth to the end of the eighteenth century. The living standard was still very low; there was as yet no large middle class and life was, for most, a dreary struggle for survival.

Then came the nineteenth century, and with it the steamengine, mass-production, and low prices. The national market needed expansion. The English and the Scotch were the first to be aware of this, and they have become since the greatest traders in the world. Others followed, for foreign trade brought wealth to the nation. This transition from a local and national self-sufficiency to a world-wide economy had farreaching results, for it destroyed the economic independence of nations and made them deeply and intricately interdependent. “International trade in the future, as in the past, will offer a very important means for raising standards of living, and humanity will be the loser if by reason of world anarchy, it proves impossible to take full advantage of this means ... Trade allows industry to adapt itself to the geographical distribution of material and human resources, and promotes the welfare of all regions by placing the demand of each in touch with the best available sources of supply.’

A British coal miner can more easily dig a ton of coal out of a mine in England than a farmer can grow a ton of wheat in a region not suited to wheat growing. The Argentine farmer gladly exchanges his surplus wheat for the Englishman’s surplus coal. Such international transactions have as their ultimate purpose the satisfaction of human needs rather than financial gain. There are several reasons why men will continue to insist on trading on a global scale. For one, the raw materials of the world are not evenly distributed. About

- Staley, op.cit., p. 246.

[Page 17] The Basis of a Planetary Economy 17

The Basis of a Planetary Economy 17

80% of the world’s known coal deposits are located in North America and Europe, inhabited by only a quarter of the world’s population. Six countries produce more than 90% of the world’s supply of crude oil. Two-thirds of the world’s supply of copper is mined in the United States and Chile, while Canada, with less than 1% of the world’s population, produces 85% of the world’s nickel. Our modern telephone system, using 37 different materials, would not have been possible without access to the far corners of the globe. The Automobile Manuiacturers Association of the United States printed, superimposed on a map of the world, 183 essential materials to illustrate that almost every country of the world contributed something to the making of the American car.

Differences of climate and soil are another reason for world trade. The rubber tree and sugar cane are native to the tropics. Coffee and tea do not grow in countries where most of it is consumed. For 90% of the world’s cotton crop we depend on the United States, India, China, and Egypt.

Density of population is another contributory factor for regional specialization and world trade. While Australia has only 2 inhabitants per square mile, Japan proper has about 470, Canada 3, Germany 370, and the Netherlands more than 600. Density of population is one reason for Chinese handmade rugs, while a thin-spread population explains Canada’s mechanized agriculture.

‘Mass-production and access to wide markets have changed

man’s standard of living. Domestic and foreign trade are now

functionally connected. “Every national industrial system

as now constituted, is synchronized with every other national

industrial system in greater or less degree through an interdependence that has evolved slowly as the countries themselves have developed. National industrial systems depend

[Page 18] 18 _ This Earth One Country

18 _ This Earth One Country

upon one another for markets, for financing, and for raw materials.’”*

The world has been knit into one gigantic economic fabric.” Modern industry has outgrown the national frontier, as at an earlier period it outgrew the boundaries of city-states. If international trade were suddenly to cease, the populations of many countries would starve and other countries would have to close their factories. Fear, misery, and desperation would follow.

Tuer Proptem or PoxiticaL BoUNDARIES

In the sixteenth century the most important trade route of Central Europe was the Rhine. Every nine miles goods had to pass a frontier and pay customs duty: Even a hundred years ago Germany was divided by thirty-eight customs boundaries, and from Berlin to Switzerland one had to pass through ten states paying ten transit duties. In 1787 farmers of New Jersey were charged duties for any products they wanted to sell in New York. Connecticut merchants boycotted New York, and Boston refused to buy Rhode Island grain.

But steady progress has pushed back the frontiers and created the mightier and more prosperous national state. While national boundaries still exist, the economic advantage derived from free movement within larger units has been fully demonstrated.

Economic forces released by the inventive genius of scientists continued to expand and transcend national frontiers, a tendency which was strongly resisted by political

- Hugh B. Killough, International Trade, N. Y., McGraw Hill, 1938, p. 23.

~

[Page 19] The Basis of a Planetary Economy : 19

The Basis of a Planetary Economy : 19

interests. National education and the press conspired with them, stressing the vital interests of “our” country. The political interests of the nation-state became diametrically opposed to the economic interests of its inhabitants. Political power was increased at the expense of the living standard of large masses of people. Economic problems were treated as national problems without regard for the neighbors across the border. An apparent solution in one country cancelled all efforts in another. The economic war was on.

The expansion of imperialism in the late nineteenth century may be explained as a political adjustment to technological and economic changes. As the sovereign national unit became too cramped for economic activity, new territories were sought and seized, a policy which has been largely responsible

’ for our recent wars.

“The motive for conquest will be lessened by anything that reduces the economic importance of political boundaries. That, in the final analysis, is the only road to equitable adjustment for territorial claims based on a desire for better economic opportunities. To seek adjustment merely by shifting territory from one sovereignty to another, leaving it the exclusive economic preserve of State B instead of State A, treats the interests of the rest of the world as badly as before and does little to remove the seeds of recurring conflict. The real problem for economic welfare and for peace is to make political boundaries less significant economically — that is, less significant as barriers to the best social use of resources.’”*

Tur OBSTACLE OF TARIFFS

The advantage of foreign trade is that goods can be imported at a lower price than they would cost if produced

“Staley, op.cit., p. 295.

[Page 20] 20 z This Earth One Country

20 z This Earth One Country

at home. If tariffs are raised high enough to equalize the difference in cost of production between home and abroad, the advantage is cancelled and trade ceases. The popular fear of high-standard countries that they cannot compete against lower-wage countries has little, if any, real justification. With the highest wages in the world, the United States is the second largest exporting country. The fact that the American car, made with three times higher wages, undersells any other automobile manufacturer in the world is one of many illustrations that efficient adaptation of tools and resources can outweigh the factor of cheap labor.

Tf the introduction of a new labor-saving device reduces the cost of an article, and the benefit is passed on to the consumer, the economic advantage is evident. The same is true if the saving is derived through importation from a lower-wage country. The campaigns which have been waged for the exclusion of foreign manufactured goods were on the whole as costly to the people as if the introduction of new labor-saving machines, such as the steam shovel, had been suppressed. In either case, displaced labor in the old industry had to find new occupation, but the transition cost paid in the end.

From the point of view of world economic welfare the industries of every country fall under three categories:

Export Industries. This group includes all industries best suited to the country’s resources, population, and climate, which can compete successfully in the world’s markets.

Domestic Industries. This group consists of regional utilities and services such as construction, transportation, sanitation, and truck marketing which, by their very nature, are

limited to a certain territory.

[Page 21] The Basis of a Planetary Economy - 21

The Basis of a Planetary Economy - 21

Subsidized Industries. This group came into existence through protective tariffs and is the result of a short-sighted policy, frequently sponsored by vested interests at the expense of the people. Less efficient industries are actually subsidized by the consumers, for they are paying more than they would for the same articles imported from more efficient export industries of other countries.

‘These subsidized industries hurt not. only the export business of foreign countries whose products their protective tariff excludes, but also their own export industries which are handicapped by retaliatory measures. For no country can export unless it imports. Under any national economic policy many foreign export industries are sacrificed for the benefit of a subsidized group at the risk of world peace. When one country or an empire has monopoly over certain raw materials, the temptation to exploit the consumers in the rest of the world is difficult to resist. This policy also invites measures of retaliation, and then it is already too late to control, much less to halt, the vicious circle thus started.

The unprecedented economic and financial progress of the

United States of America since federation is one of the classic

examples of the development of free trade. In 1789 the

original thirteen states had worthless currencies and a foreign

and domestic debt of over $54,000,000. Within ten years

they quadrupled their foreign trade and by 1835 distributed

a surplus of nearly $37,500,000. Slave labor in the South contributed to the great difference in the standard of living of the

various states. The high-standard states did not have to

sacrifice anything to those of a lower level of living in spite

of the removal of all tariffs; on the contrary, free trade raised

both the lower and the higher standards. And if the tariff

barriers had not been removed, the forty-eight American

[Page 22] 22, - This Earth One Country

22, - This Earth One Country

States of today would not be driving about 82% of the world’s motor vehicles. “It can be proved that . . . the unrestricted international exchange of goods increases the real incomes of all the participating countries.”

“Economists are prepared to demonstrate that free trade between national communities brings more effective production and increases the economic welfare not only of the world as a whole and of the dominant trading nation, but of all the nations participating in the freer trading system.”®

Frese Enterprise Versus CoLtuEctTivE PLANNING

Christianity has always stressed the dignity of human personality and the sacredness of individual conscience. Protestantism, as a consequence of its long struggle with and final separation from its mother-church, has laid great emphasis on the freedom of the individual. The rugged individualist of the industrial era became so absorbed in his struggle for freedom that he forgot the art of losing his own self for something greater and nobler than himself. This obsession for laissez faire went so far that the individual eventually lost interest in the freedom of his fellows. At the same-time, — powerful nations resented with righteous indignation the aspirations of enslaved people.

The Socialist movement, spontaneously supported by millions, arose in protest. Its fundamental aim is the abolition of poverty, the attainment of economic security, and a greater equalization of income. It hopes to achieve this through

°G. Haberler, The Theory of International Trade, N. Y., Macmillan, 1987, p. 221.

- J. B. Condliffe, The Reconstruction of World Trade, N. Y., W. W. Norton, 1940, p. 120.

The Basis of a Planetary Economy 23 government planning and common ownership and control of the means of production. To this end, it wants to abolish the. institution of private property, as distinguished from personal property. The more moderate Socialists are willing to leave smaller enterprises in private hands, as long as they do not conflict with the interests of the common man.

The opponents of state control believe that under socialism initiative and freedom of enterprise would be lost. In capitalist countries private enterprise subsists on the hope of gain and the risk of loss. It seizes on every new idea likely to cheapen costs and enlarge turnover; it stimulates invention, originality of method and boldness, qualities which the red tape of government offices tends to hamper and stifle. Under this system, fair but energetic rivalry eliminates the inefficient and unprogressive enterprise. Capitalism gives scope to the spirit of the adventurer who, pursuing his creative impulse, finds freedom for individual expression by making decisions and taking risks from which any committee or government department would shrink.

On the other hand, we must not overlook the phenomenal rise of modern corporations controlled by managers who do not own them. These are usually more efficiently run than small businesses and up to a certain point, as Professor W. L. Crum of Harvard has shown, “the larger the corporation, the higher the rate of return” on capital investment. Competition and its advantages are gradually removed by these corporations, owned by absentee stockholders. Being monopolistic in tendency, these corporations will continue to grow and, if not checked, will eat into the domain of the independent operator, thus preparing the way for the state to assume

control.

During the last hundred years, in spite of the controversy

[Page 24] 24 This Earth One Country SS

between free enterprise and socialism, modern states have

been forced, whether liberal or reactionary, to take over much

of the direction and operation of economic activities. The

laissez faire theory of the nineteenth century liberals, that

the greatest economic welfare can be achieved only by privately owned and controlled enterprise, operating all over the

world with the least possible government interference, has

been rejected. Government control has come to stay, for the

interpenetration of economic and political forces has gone

too far. “The chief characteristic of change in the organization

of society in the last half-century,” writes Professor Ohlin,

“has been the growth of central organization and control.”

Many contemporary economists are searching for a working compromise between state regulation and free enterprise.

“Apart from the Soviet Union — which falls into a category

of its own —the countries of the world are at present attempting to find some half-way house between laissez faire

and collectivism; some system which shall as far as possible

avoid the disadvantages and combine the benefits of both

individual enterprise and management by the State.’

These mixed systems, as operated at present, unfortunately

do not supply good testing ground. Planning directed by

sovereign states for political or military reasons tends to be

restrictive, whereas private enterprise is losing the stimulation of fair competition and inclines increasingly towards

monopoly. Protective tariffs and import quotas, often extended in return for political consideration, are as harmful

to planetary welfare as are monopolistic combinations within

the state. Lacking a supranational organization, all economic

24 This Earth One Country SS

between free enterprise and socialism, modern states have

been forced, whether liberal or reactionary, to take over much

of the direction and operation of economic activities. The

laissez faire theory of the nineteenth century liberals, that

the greatest economic welfare can be achieved only by privately owned and controlled enterprise, operating all over the

world with the least possible government interference, has

been rejected. Government control has come to stay, for the

interpenetration of economic and political forces has gone

too far. “The chief characteristic of change in the organization

of society in the last half-century,” writes Professor Ohlin,

“has been the growth of central organization and control.”

Many contemporary economists are searching for a working compromise between state regulation and free enterprise.

“Apart from the Soviet Union — which falls into a category

of its own —the countries of the world are at present attempting to find some half-way house between laissez faire

and collectivism; some system which shall as far as possible

avoid the disadvantages and combine the benefits of both

individual enterprise and management by the State.’

These mixed systems, as operated at present, unfortunately

do not supply good testing ground. Planning directed by

sovereign states for political or military reasons tends to be

restrictive, whereas private enterprise is losing the stimulation of fair competition and inclines increasingly towards

monopoly. Protective tariffs and import quotas, often extended in return for political consideration, are as harmful

to planetary welfare as are monopolistic combinations within

the state. Lacking a supranational organization, all economic

"Bertil Ohlin, The Future of Economic Organization, in the Sir Halley

Stewart Lectures, 1937, London, George Allen & Unwin Ltd., 1938, p. 66.

°P. W. Martin, International Labour Review, Vol. 25, Feb. 1937, p. 180.

[Page 25]

The Basis of a Planetary Economy 25

planning, not excepting that of a Socialist government, is by necessity national, even though the problem is international.

An ideal combination of free enterprise and state-control _ would necessitate the total elimination of all monopolies or special privileges within and between each nation, as other- wise no government planning can remove economic and political conflict.

WELFARE oR PowrER Economy

The difference between welfare and power economy is the difference between production for civilian or military use. Undisturbed peace economy could produce enough to abolish poverty everywhere and raise the level of prosperity to heights undreamed of before, provided the goods of the world could move across political boundaries unhindered. Trade barriers breed rivalry over export markets, engender insecurity in domestic affairs, and place a high premium on political control of colonial possessions. A country controlling an important share of the world’s resources invites aggression, if it refuses to trade with the rest of the world. This fear of aggression causes nations to follow a power economy rather than a welfare economy.

In a world of sovereign states war is not only possible but

inevitable, and a nation’s economy has to be geared to the

war machine. Its economic policy will tend towards selfsufficiency. For national security, it will encourage the establishment of economically unsound industries. France, for

instance, subsidized at great expense the creation of its own

dyestuff industry to have, in case of war, enough poison gas

and explosives. French peasants were supported to grow

wheat at three times the cost of American grain as a precaution against submarine blockade. Germany preferred to pay

[Page 26]

26 "This Earth One Country

almost four times as much for synthetic as for natural oil, and twice as much for artificial rubber, while the price of raw rubber fell heavily in the world’s markets. At enormous costs to the population, whole industries were either moved to strategic points, or were newly established. And all this for the purpose of conquering or to prevent conquest.

From the point of view of welfare economy it is a good policy to buy abroad for less what would cost more to produce at home. From the point of view of war economy each nation tries to become self-sufficient, regardless of cost. As long as each nation has to depend on its own resources for its defense, this vicious circle cannot be stopped. To the astronomical cost of the war itself and its aftermath should be added the invisible and incalculable cost of power economy, which is too immense to estimate.

There is a characteristic difference between the pursuit of

power economy and welfare economy. Welfare economy is

co-operative; it enriches all. Power economy is vicious, for

gain to one is loss to another. International conflict in the

pursuit of either welfare or power economy is possible, but

with this difference: a conflict between two nations pursuing

welfare economy in relationship to each other, such as

Canada and the United States, or Sweden and Norway, can

always be settled around a table; if necessary, by compromise. Common sense dictates that war is not worth the cost.

But in case of conflict between nations pursuing a policy of

power economy this is not possible, for even the suggestion of

compromise can be interpreted as weakness, which means

loss of prestige. Nations that build their prestige on power

in relationship to each other cannot yield. When it comes to

a conflict, they must fight it out. ’Abdu’l-Bahaé once compared

a peace conference of national governments, proud of their

[Page 27] é

é

The Basis of a Planetary Economy . 27

tradition and power, to a meeting of wine merchants in support of prohibition. ~

No policy of power economy will be abandoned until each nation feels free from aggression. The measure of success or failure of any postwar plan can be determined to the extent that welfare economy will replace power economy.

The people of all nations are now part of one economically interdependent world. No single nation can be prosperous if the rest of the world is poor, and no one country can enjoy peace if the rest of the world is at war. A larger view, a world approach, is, therefore, necessary if our problems are to be resolved. “The welfare of the part means the welfare of the whole, and the distress of the part brings distress to the whole . . . The interdependence of the peoples and nations of the earth, whatever the leaders of the divisive forces of the world may say or do, is already an accomplished fact. Its

unity in the economic sphere is now understood and recognized.”

This interdependence cannot be regulated without a corresponding political integration. Recognizing this fact, we must look at the political aspects of man’s immediate future. The establishment of some kind of supranational organization is, in the light of events, a foregone conclusion.

° Shoghi Effendi, The Promised Day Is Come, Wilmette, Ill., Bahé’i Publishing Committee, 1941, p. 127.